Human history dramatically shifted with the advent of writing systems. No longer reliant solely on oral tradition, societies could record events, codify laws, and transmit knowledge across generations and vast distances. Pinpointing the precise moment writing emerged, however, proves challenging. Archaeological discoveries continually refine our understanding, revealing a complex and diverse tapestry of early writing practices across the globe. This article explores the chronological emergence of writing systems, focusing on key regions and examining the evolutionary pathways that led to this pivotal technological advancement.

Mesopotamia, the land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, often claims the title of birthplace of writing. Evidence suggests that proto-cuneiform, a precursor to cuneiform script, began appearing around 3200 BCE. Initially, this system employed pictographic symbols representing objects. Over time, these symbols evolved into increasingly abstract signs, representing syllables and eventually, sounds. The clay tablets unearthed at sites like Uruk demonstrate the gradual shift from pictorial representation to a more sophisticated system capable of encoding complex ideas and narratives. This development marked a profound cognitive leap, facilitating the administration of large-scale agricultural societies, economic transactions, and the recording of legal codes like the Code of Hammurabi. The longevity of cuneiform, persisting for over three millennia, underscores its impact on subsequent writing systems in the Near East.

Moving eastward, the Indus Valley Civilization, flourishing between 2600 and 1900 BCE, presents a fascinating, yet still partially enigmatic, case study. While the Indus script remains undeciphered, thousands of inscribed seals and pottery fragments attest to a sophisticated writing system. Its unique character, differing significantly from other contemporary scripts, suggests an independent development. The script’s complexity and widespread distribution across a large geographical area point to a developed administrative structure and a high degree of social organization. Ongoing research continues to decipher its meaning, potentially revealing insights into the societal structures and worldview of this remarkable civilization.

In ancient Egypt, hieroglyphs emerged around 3200 BCE, concurrently with the development of cuneiform. Initially also pictographic, Egyptian hieroglyphs gradually developed into a more complex system combining logograms (symbols representing words) and phonograms (symbols representing sounds). Hieroglyphs adorned monumental structures, adorned tombs, and were used for religious texts, providing a rich source of information on Egyptian society, beliefs, and history. The evolution of hieroglyphs led to hieratic and demotic scripts, simpler cursive forms used for everyday writing. The Rosetta Stone, famously discovered in 1799, provided the key to deciphering hieroglyphs, opening a window into the history of ancient Egypt.

Across the Aegean Sea, the Minoan civilization of Crete flourished from approximately 2700 to 1450 BCE, developing a unique writing system known as Linear A. This syllabic script, unlike cuneiform or Egyptian hieroglyphs, seems to have emerged independently. Though still undeciphered, Linear A inscriptions on clay tablets and other artifacts offer glimpses into Minoan society, administration, and trade networks. Linear A eventually gave way to Linear B, a script deciphered in the mid-20th century. Linear B, used by the Mycenaeans, proved to be an early form of Greek, revealing valuable information about the Mycenaean world and its relationship to later Greek civilization.

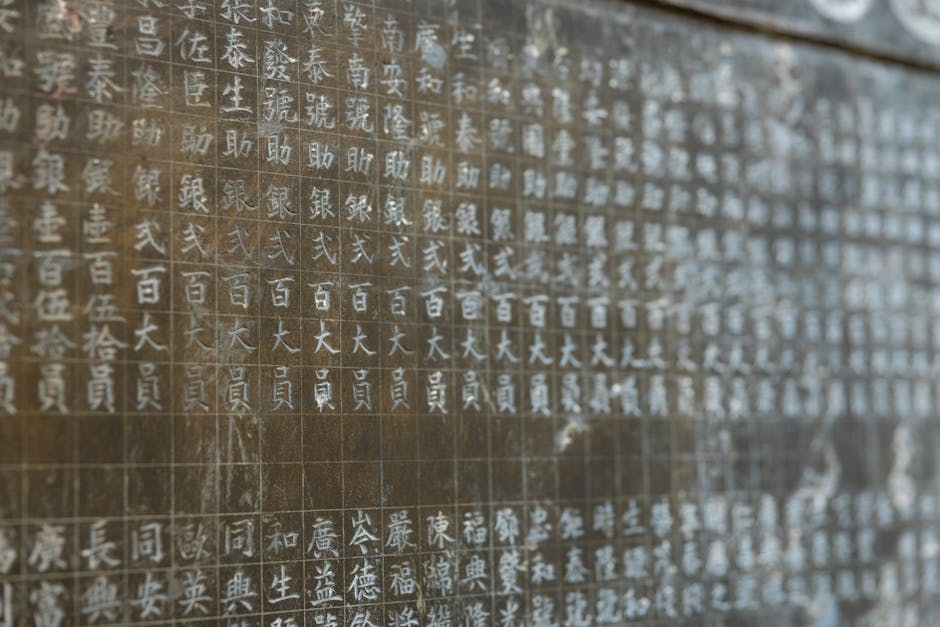

In East Asia, the emergence of writing systems followed a different trajectory. China’s earliest known writing system, dating back to around 1200 BCE, appeared during the Shang dynasty. Oracle bone inscriptions, etched on animal bones and tortoise shells, were used for divination. These inscriptions employed a logographic system, where each character represented a word or concept. The development of Chinese writing represents a remarkable achievement, with the system’s evolution continuing over millennia, leading to the highly sophisticated writing system used today.

Central America offers another remarkable example of independent development. The Olmec civilization, flourishing from around 1200 BCE to 400 BCE, developed a complex system of writing, although its full extent and nature are still being investigated. Subsequent Mesoamerican cultures, including the Maya and the Zapotec, further refined and adapted the writing systems, creating sophisticated calendars, recording historical events, and preserving religious texts. The Maya script, notable for its intricate glyphs, remains one of the most complex writing systems ever developed, providing invaluable insights into their sophisticated culture and astronomical knowledge.

In summary, the emergence of writing was not a singular event but a process of independent invention and adaptation occurring across various parts of the globe. While Mesopotamia and Egypt often receive primary attention, the simultaneous or subsequent development of writing in the Indus Valley, Crete, China, and Mesoamerica showcases the human capacity for innovation and the diverse paths toward symbolic representation. Archaeological research continually reveals new evidence, pushing back the dates of early writing and enriching our understanding of its emergence and evolution. The complexity and diversity of these early writing systems provide a testament to the human ingenuity and cultural achievements of ancient civilizations. Further research, particularly in deciphering undeciphered scripts like Linear A and the Indus script, promises to further illuminate the origins and spread of this transformative human invention.