The advent of the printing press, a seemingly simple mechanical device, fundamentally reshaped the landscape of literature. Its influence transcended the purely mechanical, impacting everything from the accessibility of texts to the very nature of authorship and the evolution of literary genres. This article explores the profound and multifaceted ways in which the printing press revolutionized literature, examining how it altered the production, distribution, and consumption of written works.

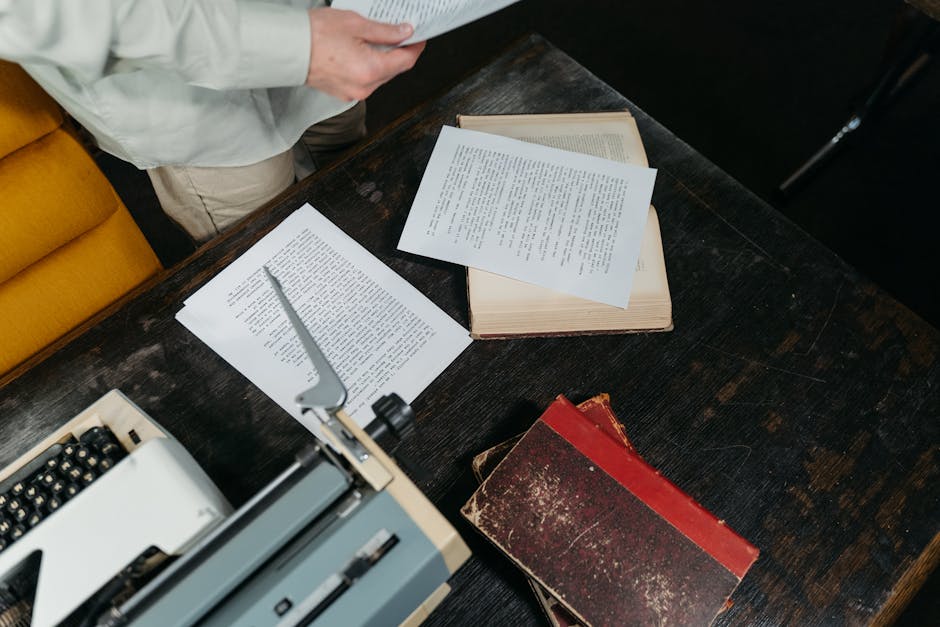

Before the printing press, books were painstakingly hand-copied, a laborious process often reserved for monasteries and wealthy individuals. This limited both the availability and the diversity of literary works. A single manuscript could take months, even years, to complete, making access to knowledge and creative expression highly restricted. The handwritten texts, often adorned with elaborate illustrations and unique embellishments, were intrinsically linked to the creator’s identity, their individuality embedded within the very substance of the book. This singular production method also meant that variations existed between different copies, and the standardization that became a hallmark of the printed text was absent.

The printing press, spearheaded by Johannes Gutenberg’s revolutionary invention in the mid-15th century, introduced a completely different paradigm. The mechanized reproduction process drastically accelerated the production rate of texts. The ability to produce multiple identical copies, relatively quickly and cheaply, meant that literature, once a preserve of a select few, became increasingly accessible. This accessibility was a pivotal turning point. Books, previously considered luxury items, entered the public domain, igniting a cultural shift as literacy rates began to rise.

Furthermore, the printing press facilitated the standardization of texts. Errors inherent in handwritten copies were largely eliminated, ensuring a more consistent and accurate reproduction of literary works. This consistency was essential for the development of a shared literary canon. Readers could now access versions of texts that were remarkably similar, fostering a sense of common understanding and shared cultural experiences. This standardization also encouraged the evolution of literary criticism as authors could refer to consistently accurate versions of their works and other authors.

The distribution of literature was significantly altered by the printing press. Books, no longer confined to specific locations or individuals, could be disseminated across vast geographical distances. This facilitated the exchange of ideas and the propagation of different literary traditions across Europe and beyond. Networks of printers and booksellers emerged, transforming the literary landscape into a vibrant marketplace. With a wider reach and increased availability, the works of authors could transcend local boundaries and achieve a level of influence far exceeding that attainable through manuscript culture.

A considerable effect of the printing press was the emergence of new literary genres and forms. The sheer availability of printed materials spurred experimentation and innovation in literary expression. The rise of the novel, for example, owes a significant debt to the printing press. The ease of producing longer works, coupled with an increase in the reading public, created an environment conducive to the development of this genre, which would dominate the literary scene for centuries. Similarly, the printing press encouraged the formalization of different poetic forms.

Beyond the realm of new genres, the very nature of authorship underwent a transformation. The ability to produce numerous copies meant that authors could now earn a greater economic return from their work. This new financial incentive encouraged more individuals to pursue a life as writers, fostering a richer and more diverse literary pool of voices. It also impacted the concept of intellectual property, leading to debates about copyright and the ownership of literary creations. The printing press fostered a new marketplace of ideas, promoting discussion and debate around the concepts of authorship and originality.

In addition, the printing press sparked a renewed interest in classical literature. The availability of ancient Greek and Roman texts, previously limited in access, became widely available, influencing Renaissance humanism and the development of new philosophical and artistic ideas. The printing press’s role in facilitating the transmission of these texts was instrumental in shaping European intellectual thought.

However, the printing press was not without its drawbacks. The proliferation of printed materials also led to the spread of misinformation and the creation of spurious works. The ease of replication made it easier for unscrupulous individuals to produce counterfeit versions of texts, damaging the reputations of authors and fostering mistrust. The rise of the printing press was met with resistance in some quarters. Concerns about censorship and the control of information also came into sharp focus.

In conclusion, the printing press played a pivotal role in reshaping literature in myriad ways. From its influence on the accessibility of texts to its impact on authorship and the development of new genres, its effects were profound and multifaceted. The ability to rapidly and cheaply reproduce texts dramatically altered the dynamics of literary production, distribution, and consumption. While challenges and criticisms accompanied its widespread adoption, the printing press’s legacy on literature remains undeniable, marking a turning point in the history of written expression. The ability to disseminate ideas far and wide, to build on and transform earlier works, and to create entirely new genres has permanently altered the trajectory of literature, making it the powerful and multifaceted force we know today.