One major category of inadmissible evidence stems from concerns about its reliability. Hearsay, for instance, is frequently excluded. Hearsay is defined as an out-of-court statement offered in court to prove the truth of the matter asserted within that statement. Its inadmissibility is rooted in the difficulty of verifying the accuracy and reliability of such statements. A witness recounting what someone else told them, without the original speaker being subject to cross-examination, introduces the risk of misrepresentation, misremembering, or deliberate fabrication. While exceptions exist, such as statements made under the stress of excitement or dying declarations, the default position is exclusion. The rationale behind these exceptions lies in the belief that, under specific circumstances, the statements are inherently more reliable.

Another significant area impacting admissibility involves the competence of witnesses. A witness must possess the capacity to understand the nature of an oath and the importance of truthfully testifying. Young children, individuals with significant cognitive impairments, or those deemed incompetent due to mental illness may be considered incompetent to testify. Their testimony, even if relevant, might lack the necessary credibility to be considered reliable evidence. The assessment of competence is often made by the judge on a case-by-case basis, considering the specific abilities and limitations of the witness.

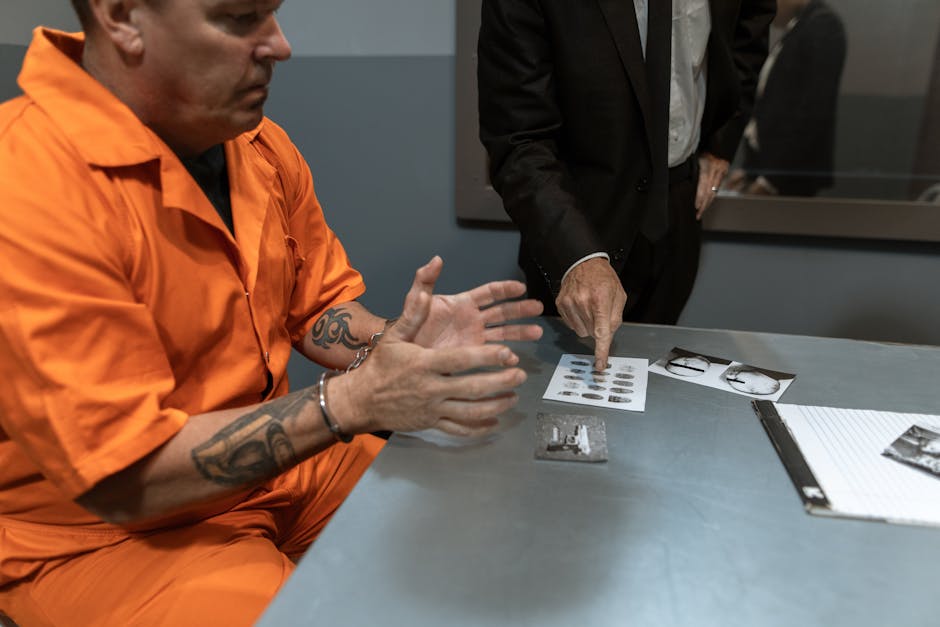

The form in which evidence is presented can also render it inadmissible. For instance, evidence obtained illegally, in violation of constitutional rights (such as the Fourth Amendment’s protection against unreasonable searches and seizures), is often excluded under the “exclusionary rule.” This rule aims to deter unlawful police conduct by removing the incentive of obtaining evidence through illegal means. The exclusion of illegally obtained evidence, regardless of its probative value, is a fundamental principle protecting individual liberties. However, exceptions exist, including the “good faith” exception, which permits the admission of evidence obtained in good faith reliance on a defective warrant.

Beyond constitutional considerations, rules of evidence dictate the admissibility of various types of evidence based on their relevance and potential for prejudice. Evidence deemed irrelevant meaning it has no tendency to make a fact more or less probable is inadmissible. Conversely, even if relevant, evidence may be excluded if its probative value is substantially outweighed by its potential to unduly prejudice, confuse, mislead the jury, or cause unnecessary delay. This balancing test allows judges to manage the flow of information in court, ensuring fairness and efficiency. For example, highly inflammatory evidence, while potentially relevant, might be excluded if its prejudicial impact surpasses its probative value.

Another factor affecting admissibility is the “best evidence rule.” This rule generally mandates the production of the original document or the best available copy when the content of a writing, recording, or photograph is in issue. This preference for original documents stems from concerns about the accuracy and authenticity of copies. Exceptions exist for situations where the original is unavailable despite diligent efforts to locate it.

Character evidence, evidence concerning a person’s character traits, generally faces strict limitations. Evidence of a defendant’s prior bad acts or criminal history is typically inadmissible to prove propensity. This is to prevent jurors from making a determination based on past behavior rather than the specific evidence presented in the current case. However, exceptions exist, particularly where the evidence is relevant to prove motive, opportunity, intent, preparation, plan, knowledge, identity, or absence of mistake. These exceptions allow the introduction of character evidence when it directly relates to a specific element of the crime charged.

Privileged communications also enjoy protection from disclosure. Several types of relationships are recognized as having a privilege of confidentiality, including attorney-client, doctor-patient, spousal, and clergy-penitent privileges. These privileges are designed to encourage open communication within these relationships, recognizing their importance for personal well-being and effective representation. The privileged party holds the right to prevent the disclosure of these communications, even if relevant to the case. However, exceptions exist, such as when the privileged communication involves future criminal conduct.

Finally, the authenticity of evidence is a prerequisite to admissibility. The proponent of the evidence bears the burden of establishing that the evidence is what it purports to be. This may involve establishing a chain of custody, demonstrating the authenticity of a document through witness testimony or other means, or verifying the identity of a speaker in a recording. Without sufficient proof of authenticity, evidence will be inadmissible, as its reliability cannot be assured.

In conclusion, the admissibility of evidence is a complex area governed by a network of rules and principles designed to ensure fairness, accuracy, and efficiency in legal proceedings. Understanding the specific circumstances under which evidence may be deemed inadmissiblewhether due to hearsay, witness incompetence, illegal procurement, irrelevance, prejudice, the best evidence rule, character evidence limitations, privilege, or lack of authenticityis essential to navigating the intricacies of the legal system. The careful application of these rules by judges serves as a crucial safeguard in the pursuit of justice.