The dawn of written communication stands as a pivotal moment in human history, marking a profound leap in cognitive capacity and societal organisation. This monumental development, independent of other cultures, emerged within various early civilizations, each forging its unique system of symbolic representation. Understanding the impetus behind this innovation, alongside the prevailing socio-cultural contexts, offers a fascinating glimpse into the ingenuity and evolutionary trajectory of human thought.

Several interconnected factors contributed to the development of writing systems in early civilizations. A burgeoning population and complex social structures often required more sophisticated methods of record-keeping than mere oral traditions could provide. The increasing need to manage resources, trade, and maintain social order fueled the evolution of systems that could permanently document information. Furthermore, the rise of centralized authority, whether in the form of temples or emerging states, demanded the creation of tools for administration and control.

Ancient Mesopotamia, cradle of civilization, provides a compelling case study. The earliest evidence of writing, dating to around 3200 BCE, originates from the fertile crescent. Initially, this proto-cuneiform consisted of simple pictographs, pictorial representations of objects and ideas. Over time, these symbols underwent a transformation, developing into more abstract forms that gradually represented sounds or syllables. The transition from pictography to logography, and eventually to syllabic writing, underscores a crucial aspect of this process: the simplification of representation. As the complexity of language increased, so did the complexity of the writing system, driven by the need for more precise communication.

The development of cuneiform writing wasn’t a solitary endeavour. Different regions and cultural groups adapted and modified the system to suit their specific linguistic needs. The complexity of the Mesopotamian writing system, with its many signs and combinations, required a significant investment in time and effort to master. This intricate skillset reinforced the status of scribes, who became crucial intermediaries between the rulers and the ruled, playing a central role in record-keeping, administration, and religious practices.

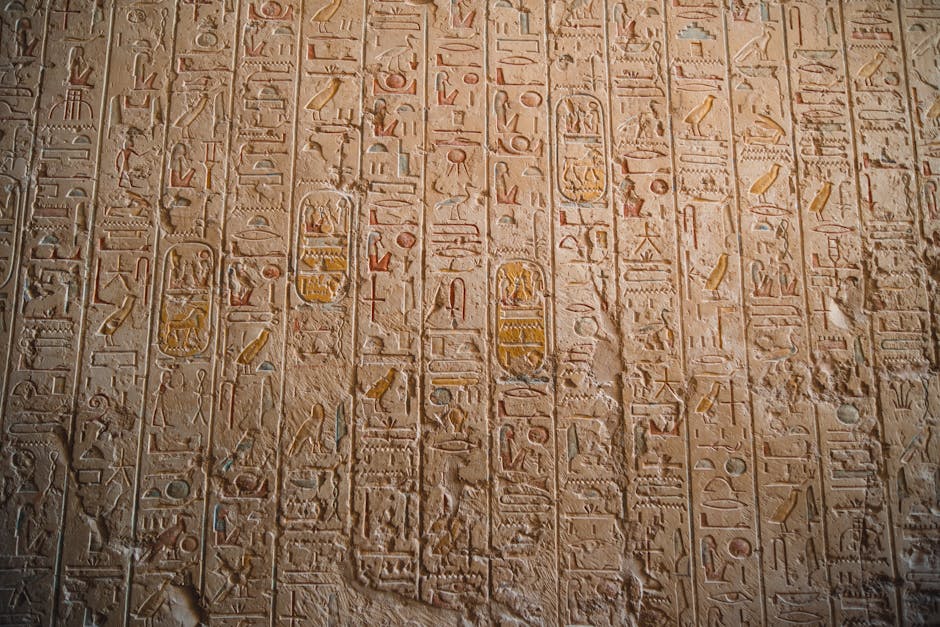

Simultaneously, other early civilizations were independently developing their own unique writing systems. In ancient Egypt, hieroglyphs emerged around 3000 BCE, a system of pictorial characters that represented objects, ideas, and sounds. Hieroglyphs were not simply a tool for record-keeping but also held a profound cultural and religious significance. Carved into stone monuments and inscribed on papyrus scrolls, they served as visual affirmations of power and the divine. The intricate detail and artistry of hieroglyphic inscriptions reveal the high esteem and cultural importance placed on this method of communication.

The complexity of Egyptian hieroglyphs distinguished them from cuneiform. The sophistication of these visual symbols demanded rigorous training and expertise, solidifying the status of scribes in Egyptian society. Furthermore, the materials used for writing, such as papyrus, contributed significantly to the development of the script, facilitating its dissemination and accessibility within the Egyptian society.

Further afield, the Indus Valley Civilization exhibited a different approach. Their writing system, discovered on seals and pottery fragments, remains largely undeciphered. The presence of a sophisticated urban civilisation, with evidence of trade and complex administrative systems, suggests the existence of a written system. These undeciphered symbols offer a fascinating glimpse into the potential diversity of early writing systems and the enduring mysteries awaiting the archaeological community.

An intriguing element of the early development of writing is the interplay between language and visual representation. Each civilization adapted the visual symbols to its specific language, reflecting a crucial adaptation process. The adaptation of signs to reflect the phonology of language wasn’t a sudden leap, but a gradual process of development. The complexities of human language, with its unique structures and nuances, heavily influenced the evolution of writing systems. The journey from simple pictographs to elaborate scripts underscores the adaptive capacity of human cognition.

It’s important to recognise that the development of writing systems was not a universal phenomenon. In many parts of the world, early societies relied on alternative methods of communication, such as oral traditions, memory aids, and symbolic objects. The absence of a written record does not necessarily equate to a lack of sophisticated communication systems; rather, it highlights the diverse range of human communicative practices.

Moreover, the specific context within which these early writing systems emerged played a pivotal role. The need for record-keeping, social order, and administrative control often spurred this innovation. The interactions between different cultures and the spread of ideas further shaped the evolutionary trajectory of these systems. The diffusion of knowledge, whether through trade routes or military conquests, provided opportunities for exchange and adaptation.

In conclusion, the development of writing systems in early civilizations represents a monumental leap forward in human cognitive capacity. Driven by a complex interplay of socio-cultural factors, these systems evolved from rudimentary pictographs to sophisticated scripts. Each civilisation, with its unique needs and circumstances, developed a writing system reflecting its specific cultural context. The investigation into these early writing systems allows us to appreciate the remarkable diversity and ingenuity of human innovation while highlighting the interconnectedness of human societies throughout history. The ongoing archaeological and linguistic research continues to reveal new insights into the fascinating and enduring legacy of early writing.