Ancient historical narratives, particularly in societies like ancient Greece and Rome, were often shaped by political agendas. Historians like Herodotus and Thucydides, while possessing remarkable observational skills for their time, presented biased accounts reflecting the values and interests of their respective city-states. Their narratives served not only to recount events but also to justify actions, celebrate heroes, and inculcate civic virtue. Myth and legend frequently intertwined with factual accounts, blurring the lines between reality and idealized representations of the past. For instance, the founding myths of Rome, while potentially containing kernels of truth, primarily aimed to solidify Roman identity and legitimacy. These early accounts lacked the critical approach and methodological rigor that characterize modern historical scholarship.

The medieval period witnessed a shift, though not a complete break, from classical traditions. Chronicles, often written by monks and clergy, dominated historical writing. These works, while valuable for their detailed records of daily life and significant events, were often colored by religious perspectives and a focus on divine providence. The emphasis on linear time and a providential interpretation of history, as seen in Augustine’s “City of God,” shaped the narrative style and content of medieval historiography. Archaeological investigation, while not absent, played a relatively minor role in shaping these narratives. The primary sources relied upon were largely textual, with limited attempts at verifying information through material evidence.

The Renaissance and the Enlightenment brought about a fundamental shift in historical thinking. Humanism, with its renewed interest in classical antiquity, fostered a more critical and rational approach to the past. Historians began to examine sources more critically, questioning their authenticity and reliability. The rise of philology, the study of language and texts, contributed to a more nuanced understanding of ancient sources. Moreover, the Enlightenment’s emphasis on reason and empirical evidence laid the groundwork for a more scientific approach to history. Thinkers like Voltaire and Gibbon demonstrated a greater skepticism towards traditional narratives, opting for a more secular and analytical perspective.

The 19th century witnessed the emergence of what is often considered modern historical scholarship. The development of archival research and the professionalization of history as an academic discipline transformed the nature of historical writing. Historians began to emphasize the importance of primary sources and rigorous methodology. The rise of nationalism also played a significant role, shaping historical narratives to support national identities and claims. This period saw the birth of “national histories” which frequently emphasized heroic figures and glorious pasts, often neglecting inconvenient truths or marginalized perspectives.

The 20th and 21st centuries have been marked by significant advances in historical methodology. The influence of social sciences, particularly anthropology and sociology, has led to a greater focus on social history, exploring the lives and experiences of ordinary people. The development of quantitative methods and the application of statistical analysis have allowed historians to analyze large datasets and identify broader patterns and trends. Postmodernism further challenged traditional notions of objectivity and truth, emphasizing the role of interpretation and perspective in historical writing. This approach acknowledges that historical narratives are not simply objective reflections of the past but are constructed interpretations shaped by the historian’s own biases, perspectives, and the historical context in which they are written.

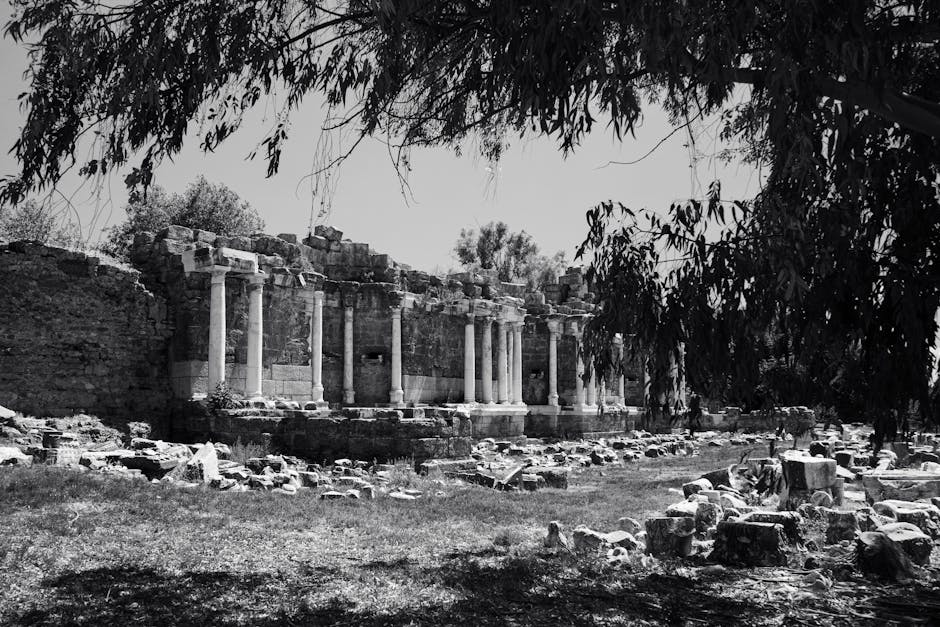

The role of archaeology in shaping historical narratives has been equally transformative. Initially, archaeological discoveries were often used to support existing historical accounts, providing tangible evidence for events or figures mentioned in textual sources. However, as archaeological methods advanced, discoveries began to challenge and even overturn established narratives. For example, the discovery of Linear B script revolutionized our understanding of Mycenaean Greece, providing insights into a civilization previously known only through legends and scattered references in Homer’s epics. Similarly, the excavation of Pompeii and Herculaneum provided invaluable insights into Roman daily life, far surpassing the limited perspectives offered by classical literature.

The development of scientific dating techniques, such as radiocarbon dating and thermoluminescence, has allowed archaeologists to establish chronological frameworks with far greater precision than previously possible. This has facilitated a more accurate and nuanced understanding of the sequence of events and the chronology of civilizations. Furthermore, advances in techniques like archaeobotany and zooarchaeology have revealed information about diet, agriculture, and the environment, enriching our understanding of past societies. The integration of archaeological data with textual sources has become increasingly crucial in constructing comprehensive and accurate historical narratives.

In conclusion, historical narratives have undergone a continuous evolution, moving from religiously influenced accounts and politically motivated chronicles to more nuanced, evidence-based interpretations. The development of historical methodology, the contributions of archaeology, and the influence of social sciences have all contributed to this transformation. While the search for objective truth remains a central goal, modern historians acknowledge the inherent subjectivity of historical interpretation. The ongoing dialogue between textual sources and archaeological evidence, coupled with a critical and reflexive approach to historical writing, ensures that our understanding of the past is continuously refined and enriched. The field of history and archaeology is a continuous process of revision and re-interpretation, constantly refining our understanding of the past.