Creating accessible spaces transcends mere compliance with building codes; it demands a profound shift in design thinking, prioritizing the needs and experiences of all users. Truly accessible architecture prioritizes inclusivity, recognizing the diverse range of abilities and disabilities present within any community. Achieving this requires a multifaceted approach that integrates universal design principles with a deep understanding of human factors and sensory experiences.

A foundational principle is universal design, a philosophy guiding the creation of products and environments usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design. This contrasts sharply with the traditional “one-size-fits-some” approach, where accessibility features are often seen as add-ons rather than integral aspects of the design. Universal design champions seven core principles: equitable use, flexibility in use, simple and intuitive use, perceptible information, tolerance for error, low physical effort, and size and space for approach and use.

Equitable use ensures the design is useful and marketable to people with diverse abilities. No user should feel excluded or disadvantaged. Flexibility in use accommodates a wide range of individual preferences and abilities. This could involve adjustable work surfaces, adaptable controls, or multiple ways to accomplish a task. Simplicity and intuitive use minimize the need for explanation or instruction. Clear visual cues, logical layouts, and easily understood controls are crucial.

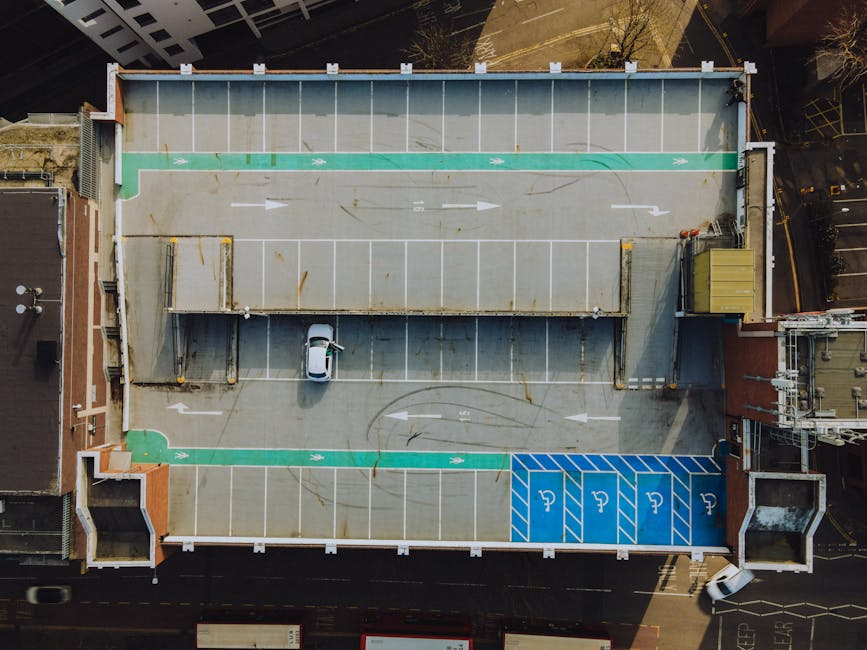

Perceptible information makes the design readily available to users with a wide range of sensory abilities. This requires clear and consistent signage, contrasting colors, tactile indicators, and auditory cues where appropriate. Tolerance for error minimizes hazards and the adverse consequences of accidental or unintended actions. Features like easy-to-reach emergency buttons and forgiving control mechanisms significantly enhance safety. Low physical effort minimizes the amount of force required to operate elements. Consideration of lever handles instead of knobs, reduced reach distances, and appropriate heights for countertops are all crucial here. Finally, size and space for approach and use provides sufficient clearance for users of all sizes and mobility devices. This includes appropriate door widths, turning radii, and maneuvering space.

Beyond universal design, specific considerations for accessibility focus on sensory experiences. Auditory accessibility, for instance, requires minimizing background noise, providing clear audio announcements, and incorporating visual cues for audio information. Visual accessibility hinges on sufficient lighting, appropriate color contrast, clear signage with large, legible fonts, and tactile elements for the visually impaired. Tactile design considers the textures and surfaces encountered, aiming for easy navigation and safe use through tactile paving, braille signage, and clearly defined edges.

Designing for cognitive accessibility is equally crucial. This involves designing for individuals with conditions like dementia or autism, whose cognitive abilities might differ. This could mean using clear and concise language in signage, avoiding overwhelming visual clutter, and providing wayfinding strategies that are easy to understand and follow. The use of consistent and predictable spatial layouts significantly aids cognitive orientation.

The incorporation of assistive technology must also be considered. Ample space should be provided to accommodate wheelchairs, walkers, and other mobility aids. Appropriate clearances around fixtures and doorways are essential, as are ramps with appropriate slopes and landings. Accessible restroom facilities, including grab bars, accessible toilets and sinks, and appropriate clearances, are a fundamental requirement. Electromagnetic fields and interference should be carefully considered to avoid disrupting assistive devices.

Material selection plays a significant role. Durable, low-maintenance materials minimize the risk of damage and reduce the need for frequent repairs, which might temporarily compromise accessibility. Non-slip surfaces are essential in areas where moisture or spills are likely. The selection of materials should also consider potential sensory sensitivities, minimizing the use of harsh textures or overly stimulating patterns.

Finally, a collaborative and participatory design process is imperative. Involving users with disabilities throughout the design stages ensures the design addresses actual needs and avoids creating unintended barriers. This inclusive approach involves consulting disability advocacy groups, conducting focus groups with potential users, and incorporating feedback from lived experience.

Successful accessible design requires more than just adhering to a checklist of regulations; it necessitates a fundamental shift in perspective. It demands empathy, creativity, and a commitment to creating environments that are not only functional and aesthetically pleasing but also truly inclusive, welcoming, and empowering for all members of society. Through careful consideration of universal design principles, attention to sensory details, thoughtful integration of assistive technologies, and a truly participatory design process, architects and designers can create spaces that foster a sense of belonging and participation for everyone. This holistic approach will lead to spaces not just meeting accessibility standards, but exceeding expectations and enriching the lives of all who inhabit them.